In the darkened room, shards of light stabbed at the blackness from beyond the windows, beating it into a hasty retreat. Breaking and entering, winter’s chill scored the fleshy cocoon of warmth that was nourished only by the soot stained furnace at the far corner of the living room. The aroma of burning petrol chemicals wafted across the room, mingling with carbon monoxide in a giddy mix.

I pulled the heavy cotton blanket up to my nose. I lay there, on the carpeted floor, pondering how I arrived at the intersection of serendipity and providence that led me to this house, as well as the myriad other possible outcomes. The weight of a day’s fatigue tugged at my eyelids, hastening me onward to a meeting with Khayyam, Rumi and the tiger of Panjshir upon the curves of a crescent moon.

Ashura, the festival of mourning, drew delegations of the Shia faithful to the city of Shiraz, Iran. Sombre black flags and pendants emblazoned with writing in Farsi were displayed prominently in the city, on buildings and cars, and in stands on the pavement. As the mid-morning sun ascended and grew in strength, disparate groups started coalescing into bigger crowds heading in a common direction.

From the distance, I could hear drums bellowing out thumps in groups of threes. These were huge drums, I learnt later, carried by the bigger men from the front with straps that crossed their backs. Young men, boys, old men and disabled men on wheelchairs, passed by in front of me as I stood to take in the scene. In their hands were flails made with short lengths of linked chains. There were others, aided by their companions, burdened with huge, cumbersome metal constructions elaborately designed with animal depictions and lined with velvet and feathers, reminiscent of battle standards.

The rows of men shuffled their feet along in separate contingents alternately chanting a song of injustice and sorrow, beating their chests and swinging the flail to flagellate themselves. White turbaned Imams ushered some groups through the procession, leading them forward to the Masjed-e Vakil in song.

I walked alongside the path, amongst the great number of spectators that had rallied to line the streets. Looking up ahead, I caught sight of a familiar face. In disbelief, I manouevred myself to get a better look. I saw another famililar face. Running to catch up, stands of planted skinny trees obstructed my view momentarily at a regular intervals, like the borders of individual frames of a movie, adding to the dream-like feel of the events I was witnessing.

I scuffled my feet along in the same direction; I mouthed the hypnotic repeating chants; I beat my chest in anguish. The three-hour walk almost had me in tears as well for Imam Hussein, the man being honoured that day. As we neared the masjid, the mood intensified, the emotions escalated, the atmosphere grew frantic, almost frenzied. There were men on horses with lances and swords, acting the tragedy of Imam Hussein’s martyrdom and the unjust slaughter of men, women and children in his camp at Karbala, Iraq, over a thousand years ago.

The massive gate of Vakil Mosque loomed ahead of us. The towers rose to the sky seemed to bend over our heads as we moved under its shadow. The central dome, a massive ovaloid head resting atop the central prayer hall, stoically observed our entrance into hallowed ground. The sprawling courtyard, bordered by the imposing blue tiled walls, were awe-inspiring. The gathering of the multitudes chanting in unison, and the echoing against the walls reinforced the feeling. At the end of the ceremony, I was invited to another mosque for a communal lunch, one exclusively serving the Hazara community in Shiraz.

Over lunch, I expressed at how alike we looked, and I expressed the same opinion. Many recounted stories of life in Afghanistan, and the prejudice they faced in Iran. In time, I was introduced to Heydadi. He had a jolly personality and a kind, warm smile on his face. He also had a tummy like jolly old Saint Nick. He was an uncle of Mohammad, a refugee from Afgahanistan who spoke English fluently. As lunch concluded, talk began to shift towards where I was staying and how I should be accomodated within the community over the duration of my visit. It was evident that having come into their circle, I now became their guest.

I was to have dinner at Heydadi’s apartment that night. Their hospitality was insistent, but I was only too glad to feign coy acceptance. Mohammad was a slightly built bespectacled man; soft spoken, cautious with an academic mien. He was respectfully attired in dress shirt and pants as is the practice in these parts. His complexion is ruddy and eyes a light brown but we shared an unmistakably oriental countenance that helped to make our conversation an easy and unguarded one.

We walked around the city, the conversation between us was casual and inquisitive. There was a genuine interest in the tone of Mohammad’s voice and line of questioning. However, his eyes never met mine. Furtive glances were thrown at all angles, detecting danger, stabbing, robbing and jeers.

In Iran, the Mongoloidal features which the Chinese like me and the people known as the Hazaras share, are a mark. The thin-slit eyes that thin out to crescent-shaped slivers of are damning features. The flat “Jacky Chan” (although Jacky Chan here is revered here, as evidenced by many Persians shouting that name in my face and smiling) noses that fan out disproportionately across the middle of the face is an indictment. The pallid, yellow skin is a branding no less dissimilar from those tattooed into the skin of prisoner camp internees.

“How can a Hazara own a camera?”

“Look at those two Hazaras.”

“What are these two Hazaras doing here?”

Their eyes hurled looks of condemnation and contempt, equalled only by poisoned words muttered in Farsi.

Mohammad quietly hurried on. I defiantly set a slower pace, standing squarely in their direction to lodge my protest. Raising my camera, I snapped a photo before hastening on after Mohammad.

At an arched entrance into an alley, bounded by high apartment walls on both sides, Mohammad stopped.

“My friend was attacked here with a knife. They took his bicycle,” said Mohammad.

“How is he now?” I asked.

“He did not survive,” Mohammad replied calmly. This calm, I realised, was not one of peaceful acceptance. It was a burdened acquiescence acquired through repeated blows at a fractured spirit.

His demeanour was his survival instinct. What I made out initially to be quietly contemplative was more fearful silence. The kind that hopes for incognito travel and undetected presence. One that hopes to blend into the background unseen. To be inobtrusive is to be unharried. Sadly, the remaining walk was a front-seat tour of other violent encounters and unfortunate incidents.

“We are immigrants here,” Mohammad reasoned.

“Without papers,” I pressed questioningly.

We ascended an unlit staircase in cold roughly finished concrete. At the fourth floor, we turned to knock the door before us. A warm light, a cosy heat and and equally sunny Heydadi emerged with a warm hug and three kisses alternated on each cheek. We were ushered to the living room where we were made comfortable. They were plush pillows tossed around the periphery of the carpet. On a mantel, there were photos of loved ones. The curtains were pulled back and tied neatly to the sides of the apartment windows. Plastic flowers adorned the corners and a portion of the walls were decorated with pictures of smiling babies.

Heydadi’s little boy was a little terror. His toys were strewn all over the floor. He was fond of screaming and insisted on getting his way. However, this toddler also had an adorable smile, and even after hitting me in the face with his red toy truck, I could only pinch his cheek adoringly which elicited more screaming and a cheeky scowl.

There was a knock on the door. “There is someone I’d like you to meet,” Heydadi said to me excitedly.

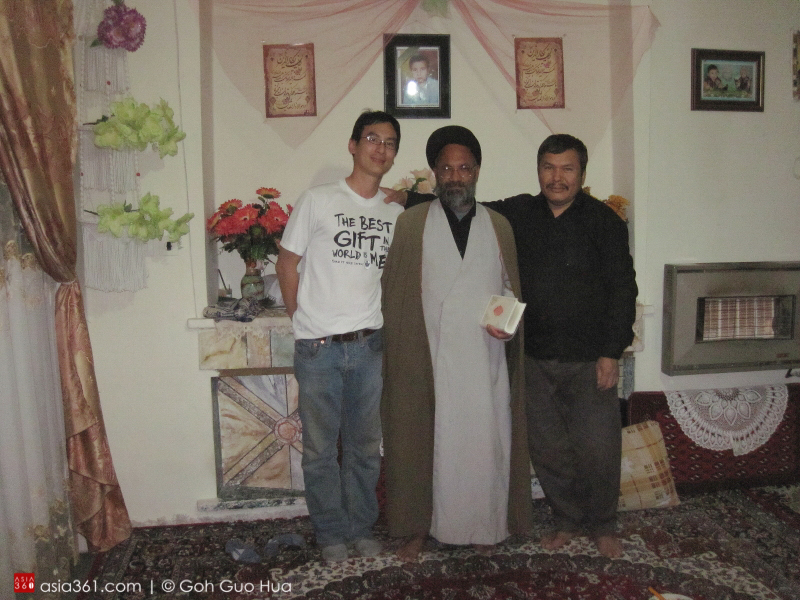

More kisses and hugs were exchanged. The new arrival had a large, round black turban. A large black shawl draped over his shoulders and spectacles lent him a scholarly look. The authoritative, learned look of an Imam. He turned his attentions to the toddler. He lifted the boy up with both hands, smiling and cooing at the child. He seated himself opposite the boy to play with the red toy truck with him. When he started throwing tantrums, the imam feigned terror, uttering “tashidam, tashidam“, recoiling in mock fear.

Over dinner, the conversations moved between topics ranging from politics to conditions back home in Afghanistan to religion. The question on religion was soon presented to me.

“What is your religion?”

Rationalising that it would be better not be considered a khafir, and justifying that I had been educated in an Anglican school for 12 years, I replied, “Christian.”

“Ah, Jesus is also our prophet,” was his reply.

I asked Mohammad about life in Afghanistan.

He spoke about the difficulties of daily life, “People don’t know whether they will see the next day. The most that they hope for is a flat bread for each meal.”

He recounted his attempts to escape from the harsh life in the country. One of his attempts at getting refugee status was to visit the American embassy at Kabul, but this was met with rifles being pointed at him and being thrown to the ground. Not being able to even make it into the embassy, he had to resort to covert means to enter Iran.

Life in Iran, he said, was much better but still very stressful, as the threat of being caught and deported was ever present. Additionally, they were not welcome by the general populace, making robberies, violent assaults and denigration an everyday occurance. He had to keep his head down and his presence unseen.

I invited him to go with me to visit the Persian splendours of Parsagarde, Cyrus’ tomb and Pesepolis which he had never seen, even in his five years in the country. It was a privilege to have been taken in so completely by the Afghan community and there is no end to the stories I could recount from those two weeks.

At the end of my stay at Heydadi’s house, I was given another special treat which came as a surprise — in a cultural context, it was a show of trust and being invited into the inner realm of the family.

The wife who had quietly prepared the night’s dinner unseen was called out. Coyly, she pulled her large shawl across her face to protect her modesty.

“I let you see my wife. Please take picture,” said Heydadi.

I did not know how to respond. I bit my tongue, but the only thing I could say was, “She’s beautiful.”

I was worried his smile would morph into a flash of anger over perceived lust. But, there was no misunderstanding forthcoming. We parted with him asking me to come again and a declaration that we were now brothers.

Two years later, on a trip to Pakistan, I contacted Mohamad vis email. He had since returned to Kabul. I spoke excitedly about my plans and the possibility of visiting. He wished me well and asked how I was doing and expressed that Mohammad was back in Kabul.At the end of the call, I pushed for a tangible invitation. “Don’t come,” was his reply.